Having great ideas is nice, it just doesn’t matter unless you can sell them to the decision-makers. As you gain skills as a designer, you’re more likely to know better than the people you report to. Often you’ll be reporting to someone who hasn’t thought deeply about your problem space, or isn’t a designer at all. It’s not enough to explain your idea the way you came up with it, you need to be able to sell the idea in a way an executive can see the value.

Designers tend to get stuck in analytical arguments, but when the stakes are high your boss will be very reluctant to greenlight any idea that makes them feel uncomfortable or they have a gut feeling won’t be fun, or won’t be worth the effort. These negative gut feelings are emotional hurdles to overcome, no matter how they manifest as analytical ones. The analytical arguments that come out of them are the symptoms of the disease. You can treat the symptoms all you like, but if you don’t treat the underlying emotional issue you will never make the sale.

So how do we overcome the underlying emotional problem? There’s a lot of techniques but here are two easy ones.

- Take them to the Sushi Restaraunt

Imagine you’re working for a catering company. The head caterer is looking for ideas of what to serve at a high class dinner function by the ocean. You suggest serving raw fish. Unfortunately, the head caterer has never heard of sushi and immediately thinks about how dangerous raw chicken and raw pork is. Plus how appetizing can raw meat be anyway? If raw meat was good, why would we need high class chefs in the first place?

No matter how much you explain the underlying food chemistry that makes sushi taste good, it’s fundamentally too foreign an idea for the head caterer to commit to it for a big event. They will have a gut-level rejection of the idea, they’ll do a quick search and discover that yes raw fish DOES have an increased chance of passing on foodborne illnesses (confirming their bias against the idea and their comparison to raw chicken), and no matter how much you talk about high quality fish tasting good raw they’ll say things like “Well then imagine how good it’d taste if it was cooked!”

This is where designers get stuck. Their boss is stuck on “modified raw chicken” instead of imagining actual sushi. You need to give them a new point of reference to think about your idea.

Instead of trying to answer all their objections, just take them to a popular Sushi Restaraunt. Once they see how all the different elements come together in practice, most of their objections will fall away. If they enjoy eating it themselves, then it’s a very easy sell – but even if they don’t like it themselves, they’ll see that many people DO enjoy eating sushi at this restaraunt. That’s huge. The discussion moves off “Is this idea dangerously insane?” to a more productive place.

So how do you do this in games? Try getting your boss to play a fun game that includes your idea. The fact they’re able to have fun in a game that includes your idea is a big win. If you can’t get them to do that, at least provide examples of games that do work this way and, if possible, a videoclip of people enjoying those games while engaging with your idea. This goes a LONG way to relax the fears of the unknown.

A related idea is to remind them of a similarity between your proposal and a part of a game that they already like. If you’re talking about menu design and your boss loves playing Fortnite, if one of Fortnite’s menus does something similar to your proposal then you can speak to a restaraunt they already love, because they can now imagine how your idea would work in a more familiar context. It’s always a good idea to become very familiar with your Boss’ favorite games. This gives you a shared framework for design discussions. - Draw sad stick figures

This one sounds like a joke but it’s not. Many proposals get rejected because your boss can’t see the value that you do. In game development we often only have enough scope to implement the top 3 ideas out of 20+ good ideas at any given time. Getting on the schedule means not just convincing your boss that the idea is good, but that it’s the MOST valuable use of your time.

Making analytical arguments triggers the part of the brain that exists to form counter-arguments, and doesn’t usually get people to change their underlying gut reactions. This is particularly challenging when convincing people about the impact of inconveniences to players, it’s much more emotionally comfortable to decide that current features or content is “good enough” and to work on exciting new stuff instead… Than to delay that exciting work in the effort to fix technically-functional stuff.

But our brains are hardwired to care about characters. Witnessing someone in distress makes us empathize for them and “get” the issue in a way that analytical arguments just don’t. Once people empathize, then they have a foundation you can build on with analytical arguments.

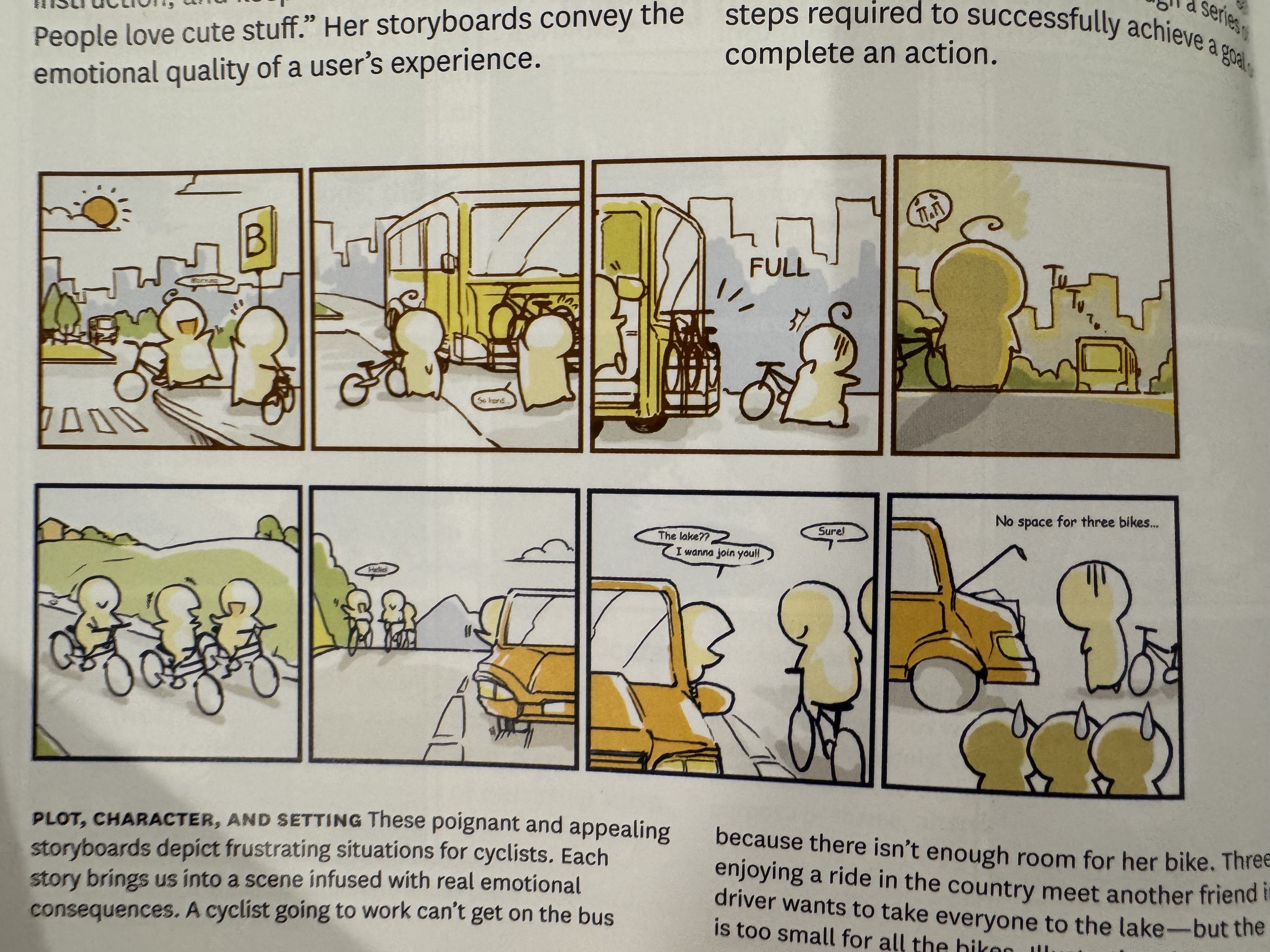

Here’s a great example from the book “Design is Storytelling” by Ellen Lupton. It shows how to convey the value of collapsible bikes, not by arguing about all their upsides directly but first by showing the issues that bicicylsts with normal bicycles face.

I’ve been amazed at how impactful it is to showcase major problems in a player’s experience by creating some simplistic stick figures on a slide deck and putting thought bubbles over their heads. You can go way simpler than these drawings, anything that looks like a human running into a problem and being understandable distressed or sad will work great.

Is this manipulative? No, it’s effective communication. People can have a very hard time understanding the perspective of a new player running into an old problem when described analytically, or understanding the impact of that negativity on their experience. Portraying that experience as directly and honestly as possible, showing them that experience, is a great solution. If you can find videoclips of players running into this issue that works great too, but if you don’t have any live players yet then an honest portrayal of the situation with a storyboard is a better way to get people to understand the problem, and to see what you see. That’s the goal of communication: shared understanding.

Picking the right technique for presenting an idea is largely about understanding the emotional issues you need to overcome. There’s a lot more than just two issues, but these are a good place to start. The first technique works for reducing fear and uncertainty around a creative solution. The second techniques works for communicating the scale of a current under-appreciated problem.